East Worlington Parish Hall

As an outcome from our learning we applied Historic Building Archaeology to our Parish Hall and utilised the evidence we have gained through our heritage project.

Glebe Terriers

The earliest record that we have of what is now known as East Worlington House is a series of “Glebe Terriers” in the Devon Record Office dating from 1605(?), 1613, 1679 and 1727. A glebe terrier is an account of church land and holdings. The two earlier documents refer only to the land, but the documents of 1679 and 1727 include descriptions of the house and curtilage. The implication of the earliest document is that the parsonage house and its curtilage were established by the early 17th century and probably had a history going back into the 16th century if not earlier still, while the later documents indicate a process of development and change at around the turn of the later 17th century.

The document of 1679, having listed the rooms of the house, concludes with a reference to outbuildings, viz:

Dairy with a chamber over it, malt house with a chamber over it, a drift (?) for drying of malt, a barn built with mud walls, a shiping (shippon) and stable.

The reference to a barn built with mud walls (presumably cob) is picked up again in the description of 1727 which states:

The outhouses are a barn consisting of five bays, a sheeping (shippon) of three bays and a stable of two bays all having mud walls and thatch covering…

Writing his East Worlington Kalendar of Quotidian Quotations in 1910, Rev. H.A.Hill was happy to accept that the barn of 1727 – and presumably also that of 1679 – was the very same that had recently been converted into a Parish Room. In 1910 the fabric, he tells us, “is the same as that described in the terrier of 1727: built of mudd and consisting of five bays.”

“The old cob walls”, he continues, “are good and of a soft and matured hue: the roof is of thatch and a pent-house over the doorway has been added and a veranda. Everything has been done in the restoration to preserve the rustic appearance and effect. An old oak window frame with deep moulded mullions was rescued from one of the village cottages, and inserted in the north wall; and two others of similar design have been put in and filled with diamond leaded panes. The courtyard in front has been paved in the old Devonshire fashion…”

This description fits nicely with an undated photograph of the building from the early part of the 20th century.

Historic Map Evidence

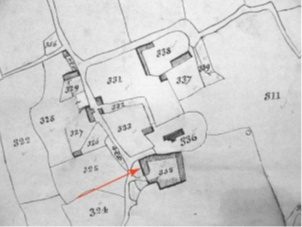

The tithe barn (Parish Hall) is indicated by an arrow in the following maps:

Extract from the East Worlington Tithe Map of 1839

Extract from the Ordnance Survey First Edition Map at a Scale of 1:2500 Published 1889

Extract from the Ordnance Survey Second Edition Map at a Scale of 1:2500 Published 1905

Roof structures

At some time in the C20th a suspended ceiling had been added which hid the original roof timbers. This was recorded in the listed building description of 1975 ‘………Interior: featureless, roof which may be of interest not seen, as concealed by a C20th ceiling…….’

The description below of the roof is taken from the Archaeologist survey and report dated 2013 and undertaken before the main hall had major conservation and improvement work between 2014 and 2016.

Archaeologist Report states:

Five A-frame trusses creating six bays. Approximately, half of the major elements of the roof structure are comprised of replacement timbers, the majority of a single modern phase, during the 20th century. The majority of the newer timbers have been bolted together suggesting a later date than for the few spiked elements, which include replacement collars and ties on the remaining early roof trusses. These spiked repairs/additions are likely to be associated with the final years of the barns agricultural use and the change to community building.

The remaining original oak timbers are confined to the northern end of the building and are comprised of the two blades of a roughly south of centre truss, the western blade of the truss to the north of this and the eastern blade of the next most northerly truss. All original purlins on both the east and west pitch of this north end remain, trenched into the backs of the earlier truss blades, and scarfed together at this point. The truss blades are set into the wall tops to east and west. All common rafters, battens and the ridge pole are modern and have been replaced during the 20th century, appearing contemporary with most of the replaced roof trusses to the south. The structure is now covered with a seemingly thin layer of thatch, with the feet of the spars protruding through for up to 0.15m. All collars and tie beams on the remaining early truss blades are replacements, bolted or spiked to the faces of the blades. The single remaining complete A-Frame truss is lapped and pegged at the apex and the former collar was affixed via face pegged notched lap-joints.

The two modern trusses to the south appear to have replaced a former single truss, the space between them is .5m -1.0m less than between the older trusses to the north.

The wall tops and the three quarter height gables are whitewashed as are the feet of the rafters suggesting they were replaced prior to the wall being painted. The majority of the roof timbers show no clear sign of ever having been painted and are not blackened. The slight modern ceiling joists have been fixed by simply gouging out a slot downward from the top of the walls and then inserting the timber.’

The photographs below show the features of the roof prior to 2014.

The conservation and improvement work completed in 2016 removed the old suspended ceiling and repaired and conserved the roof timbers exposing them to view from the hall. The photographs below show the roof timbers following the completion of the work. This gives a perspective of the layout of the hall roof when it was a barn.

Roof Covering – Thatch

Thatched roofs are perhaps associated more with the county of Devon than any other part of the country, the ‘combed wheat reed’ style of straw thatching being the traditional method of the region.

Thatching is a highly-skilled job and a good thatcher will lay the material so that water runs quickly, evenly and efficiently off the roof. The steeper the pitch of the roof, the faster rainwater runs down the stems of the thatching material and off the roof. Damp does not penetrate far into the top layer of a thatched roof in good condition; most of the thatch remains dry all the time. Unlike other roofing materials, there is no need for guttering because thatch has deep projecting eaves. This ensures that water is shed from the roof well away from the base of the walls, avoiding splash damage. Thatched roofs provide excellent insulation, keeping the house warm in winter and cool in summer.

East Worlington Parish Hall is typically thatched in the Devon vernacular as shown in the photographs below. The Hall was re-thatched in 2016.

Front View of Hall Showing Thatch with Overhang

Rear View of Hall Showing Thatch with Overhang

Wall structures

Typical Construction of Cob Walls on Buildings in Devon

Cob walls are built off a stone plinth, which can vary in height from approximately 300mm to 450mm and between 400mm and 600mm wide

Cob is a mixture of subsoil, straw and water. Traditionally, the cob would have been mixed by fork and foot or trampled overnight by bullocks. The cob mixture was traditionally placed on the plinth with a pitchfork and tread it down by foot to compact it. A layer of cob is called a lift. The first lift of cob is left to dry for a few days and then pared back into shape with a spade or mattock. The material overlapped the stone plinth by around 100mm, with surplus being removed before commencing the next layer. Further lifts are then built until the wall is high enough.

East Worlington Parish Hall Stone Plinth with Lime Mortar Supporting the Cob Walls

Exposed Cob Walls of the Parish Hall Showing the Condition and Materials Used

East Worlington Parish Hall presents these features.

The Devon saying, ‘all cob needs is a hat and a good pair of boots’, confirms the essential requirement of avoiding moisture saturation of the wall; (‘Water is the principal enemy of all earth walling’), achieved at ground level by the stone plinth and traditionally at roof level by the generous eaves overhang of a thatched roof.

Barn Doors

Barns where (and are) an essential element of the agricultural landscape. There is much debate about our barn (Parish Hall) as the whether it was originally a tithe barn, a threshing barn or a combination. There is no current evidence to support any one theory but most likely it was a general barn. It had typical barn features notably large double door located on walls opposite each other to enable fully-laden wagons to be driven into the building unloaded and driven out again.

The old barn door on the east elevation remains and is shown on the photographs below. The internal side of the door is now covered and protected by a glazed door which offers full view of the old door.

The opening for the barn door on the west elevation remains can be seen but the doors removed and externally covered by a C20th foyer extension. Both doors are visible in the photograph below.

Floor Structures

In barns of this nature many ground floors were constructed simply of compacted earth. When materials such as chalk occurred naturally in an area this was often used to harden the surface. Lime was also used in some examples.

The floor in the south end of the barn from wall to doors is natural local clay soil that has been levelled and compacted either through general usage or (more likely) beaten to form a solid surface such as those in traditional threshing floors.

The photographs show the hard-compacted surface and the white colour which suggests chalk or lime was used on the floor of our barn.

There were signs of two parallel depressions running between the doors in the east and west walls which were almost certainly the impressions of wheels on carts that would have been driven through the doors when the hall was used as a tithe barn or storage barn.

The walls to the north of the doors showed clear signs that the original floor sloped up from the level south end by about 0.75m. It seems likely that when the building was converted to its current use as a parish hall the floor was dug out to about 1.25m from the north wall to accommodate the wooden floor in the main hall area, and the hall stage was built over the remaining higher area.

This evidence supports the idea that the barn had two levels which adds to the theory that part of the barn was used for threshing and part for storage.